|

The Bike Boom From 1963 to 1973.

The following description of the bike boom was written from magazine and newspaper articles published during that time period. Special thanks to Dan Bleier of the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety for providing a copy of its 1978 publication, Bicycle-safety Education: Facts and Issues; and for permission to use its figures and tables on this website.

The High-rise 60's

|

| Webmaster's childhood 1968 Schwinn Stingray |

The bike boom in the United States was spawned in 1962 when two partners of a San Diego shop, Gene Randel and Marion Moore discovered that local kids were purchasing spare parts and building their own bicycles. These bicycles were very maneuverable because of their small frame and wheels, low profile, and high-rise handlebars. Subsequently, Randel and Moore built a few of their own for sale that Christmas season.

In early 1963, Al Fritz of Schwinn Bicycle Company in Chicago learned of these new high-risers, and had his engineering department investigate the bikes and improve on their design (e.g., banana seats). By the end of the year, 47,000 Schwinn Stingrays had been sold. Soon afterwards, all major bicycle manufacturers in the United States, including Murray Ohio, and American Machine and Foundry Company, as well as smaller bike makers such as Columbia Manufacturing Company, AMF Bicycle Division, and Stelber Cycle Corporation were producing high-risers. In addition to the Schwinn Stingray, these bikes were marketed with names such as the Avenger (American Machine and Foundry Company) and Eliminator (Murray Ohio).

Schwinn Shop |

Steering Wheel |

Radio Headlight |

Folding Feature |

Business Week 1968 Business Week 1968

|

|

|

|

| |

Business Week 1968 |

Business Week 1968 |

Business Week 1968 |

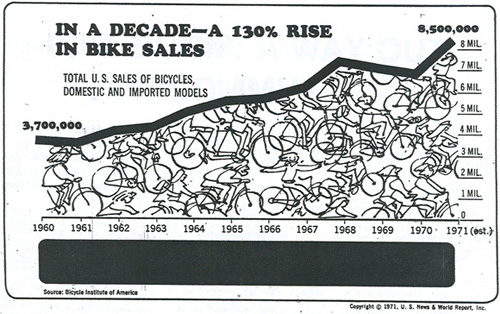

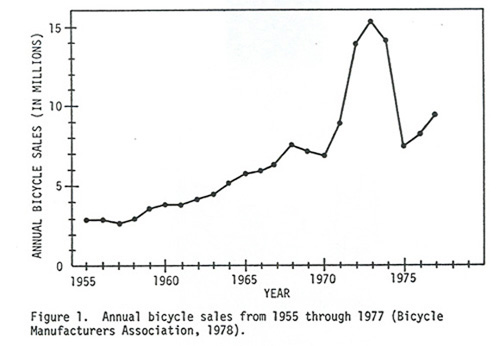

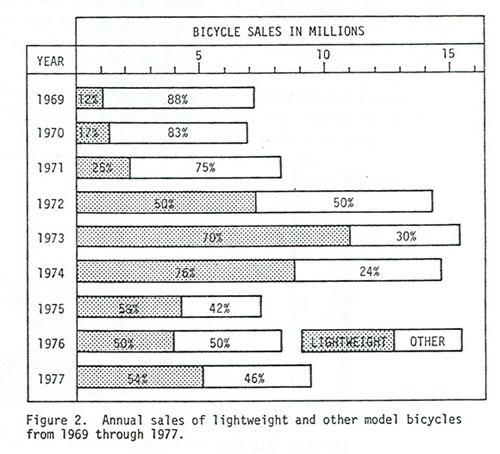

Bicycle sales steadily rose from 4 million in 1963 to 7.5 million in 1968, compared to 2.5 million in 1954. Growth during the 1950s and early 1960s was attributed to a soaring birth rate, a growing national economy, and a new grown-up market that accounted for 25% of bikes sold in 1965. The introduction of high risers fueled this growth during the 1960s. By 1968, 75% of bikes sold in the United States were high-rise models, and as a result there were many ‘two-bike boys.’ Innovations that helped sustain the growth included flamboyant colors, elongated frames, shocks, stick shifts, racing slicks, steering wheels, and gadgets such as a transistor radio headlight. This was also the time when Schwinn introduced its famous Krates (e.g., Apple Krate, Orange Krate, Lemon Peeler, and Pea Picker).

Initially, foreign manufacturers were caught off guard by the popularity of high-risers and their share of the United States market temporarily dropped from 1.3 million in 1963 to 1 million in 1964. However, foreign manufacturers soon began producing high-rise style bikes, and by 1968 despite tariffs first implemented in the early 1960s during the Kennedy administration, imports from Japan, Austria, Britain and West Germany accounted for 25% of the bike market. Nevertheless, the United States had moved from fourth to first in world bike-making. American companies advertised heavily on TV (e.g., Captain Kangaroo) and in magazines (e.g., Boys Life).

Dr. Paul Dudley |

|

Sloane 1970 |

Through the mid to late 1960s the adult market continued to grow due to a physical fitness kick, and promotion of cycling by the medical profession (e.g., Dwight D. Eisenhower’s prominent heart specialist, Dr. Paul Dudley White) as a healthy activity. Many of the adult bikes sold were lightweight English-style racers. As this adult market grew in the United States, so did concerns about quality control and service. Manufacturers relied on numerous suppliers, derailleurs were becoming more complex, and some replacement parts were hard to come by (e.g., metric-thread screws). During this period, many cities such as New York, Boston, Chicago, and Milwaukee began building bike trails and bikeways to accommodate cyclists. From 1968 to 1970, sales dipped as the bike industry transitioned from kids' high-risers to adults' racers.

Bike Boom Images From The 1960s

Look 1964 Look 1964

|

Look 1964 Look 1964

|

Look 1964 Look 1964

|

Look 1964 Look 1964

|

Central Park, New York City

Business Week 1968 Business Week 1968 |

Central Park, New York City

Business Week 1968 |

Central Park, New York City

Business Week 1968 Business Week 1968 |

Central Park, New York City

Business Week 1968 Business Week 1968 |

Central Park, New York City

Business Week 1968 Business Week 1968

|

Central Park, New York City

Business Week 1968 Business Week 1968

|

|

|

The Lightweight 70's

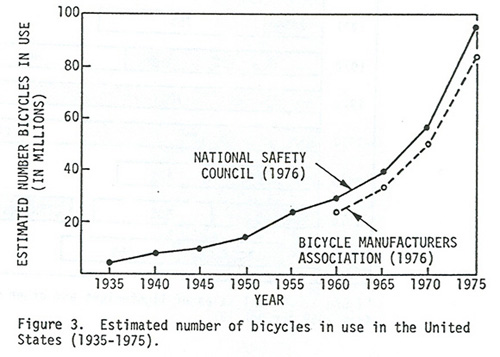

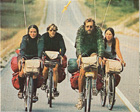

In just three years from 1970 to 1973, annual bike sales dramatically increased from 7,000,000 to over 15,000,000, with another 14,000,000 sold in 1974. A number of factors are thought to have contributed to this explosion; and ‘discovery’ of the lightweight 10-speed that took hold during this period was one of the most important. These multi-sprocket bikes allowed adults to cycle long distances and climb steep-grades more easily than on other more traditional types. By this time, the youth market was pretty much saturated with 80% of 5 to 15-year olds owning bikes, but the adult market was seemingly unlimited. From 1970 to 1973, the percentage of bikes sold to adults increased from 15% to over 50%, and the percentage of lightweights from 17% to 70%. In 1972, for the first time since World War II, more bikes were made than automobiles!

Cycling was thought to be healthy, increasing circulation in the legs, reducing the risk of heart disease and arteriosclerosis, and alleviating stress and mental fatigue. Cycling was an alternative means of commuting that was not affected by the gas shortage or recession, and was good for the environment. In New York, companies such as Con Edison and Union Carbide installed bike racks for employees. Charismatic Mayor Lindsey of New York and Mayor Daley of Chicago ‘swore fealty’ to bikes, and more than fifty cities including San Diego, Davis, Denver, St. Louis, and Cambridge began planning urban bikeways. Bikeways were also being planned by states, most notably Wisconsin in which a 300 mile bikeway was built across the state. In 1973, 250 pieces of legislation were introduced in 43 states, and federal and state monies were being allocated for construction of footpaths, bike paths and bike lanes. New sources of money for these projects included the Highway Trust Fund, state highway funds, and gasoline taxes. Cycling races were becoming more prominent with over 400 annual events in the United States including the infamous Mt. Evans climb from foot to peak (my oldest brother participated in this event).

|

Unfortunately, the peak of the bike boom from 1971 to 1972 caused severe supply shortages. The bicycle industry fell short of demand by 2 million bikes from May to October of 1971. For example, Schwinn retailers sold out of 1,225,000 units and Schwinn Bicycle Co. booked orders for the entire year by May. Foreign producers in Austria, Britain, West Germany and other countries which accounted for one-third of the U.S. bike market were also unprepared for the surge in demand. In addition, Japan which was the leading importer accounting for twenty-seven percent of the foreign segment in 1970, had voluntarily limited the annual growth of Japanese imports such as American Eagle in the U.S. market to 10% due to pressure from Washington. There were parts shortages as well, with gears from France, handbrakes from Switzerland, tires from Britain, and saddles from Italy not keeping up with manufacturing needs. All of these factors resulted in backorders and long delays in delivery.

The publishing industry was also taken by surprise. “The Complete Book of Bicycling” by Eugene Sloane which was first published in 1970 sold 33,000 copies and was in its 7th printing in just one year. By 1973 the bicycle shortage was over because of a slight dip in sales, an increase in U.S. production, and an increase in imports from Japan and to a lesser extent Taiwan, Korea, India, Romania, France, England, Italy and West Germany. From 1972 to 1973, American made bicycle sales rose from 8.8 to 10.4 million, of the 13.9 million sold in the U.S. due to devaluation of the dollar.

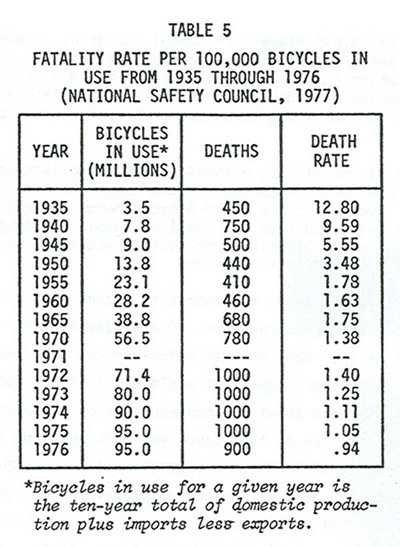

The peak in the bike boom was accompanied by security and safety concerns. In major cities, the number of stolen bicycles increased by 30% from 1970 to 1971, and another 35% from 1971 to 1972. For example, in Los Angeles bike thefts increased from 7,600 in 1969 to 12,500 in 1971. Not only was an increase in the number of bicycles attractive to thieves, but also an increase in their worth. While a $125 bicycle might bring $25 on the black-market, a $500 bicycle could fetch $200 or more. Compounding the situation was that many owners did not know the serial number on their bicycles, and in some cases not even the model numbers. As a result, many cities including Chicago, Pittsburgh and New Orleans, as well as Dade County instituted mandatory registration programs. In addition, bicycle shops and owners were etching serial numbers into the frames. The large number of bicycles ridden by adults, especially commuters was also becoming a problem. Riders were competing with cars for roads and space, and not always following traffic laws. The number of riders killed nationally in 1971 and 1972 was estimated to be 850 and 880, respectively, compared to 490 in 1961. Proponents of bicycling used these statistics to push for greater law enforcement and more bike lanes, paths and trails.

By 1975 the bike boom had subsided. Some attribute this leveling-off to the end of the nation’s fuel crisis of 1973 and 1974. Although bicycle sales continued to rise steadily through the 1970s from 7.3 million in 1975 to 9.3 million in 1978, the more than doubling of sales in just three years during the early 1970s was never to be matched.

Bike Boom Images From The 1970s

Yukon, Canada

National Geographic 1973 National Geographic 1973

|

Alaska

National Geographic 1973 National Geographic 1973

|

Alaska

National Geographic 1973 National Geographic 1973

|

|

U.S. News & World Report 1973 U.S. News & World Report 1973 |

U.S. News & World Report 1973 U.S. News & World Report 1973 |

|

|

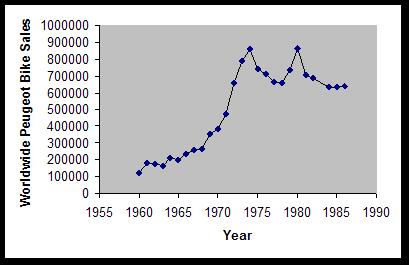

The Peugeot Bike Boom

Peugeot bicycle production during the 1960s and 1970s paralleled the bike boom trend, with sales steadily rising during the 1960s, and then dramatically increasing from 1970 to 1973, followed by a decline in 1975. Prior to 1972, Peugeot bicycles were built in Beaulieu, France. In 1972, Peugeot built a second manufacturing facility in Romilly-sur-Seine, and became the French bicycle leader with 458,000 domestic sales and 390,000 exports in 1974. Motobecane was the nearest rival with 420,000 domestic sales and 180,000 exports. In the United States, the leading importer of bicycles was Japan, followed by Austria and Great Britain, and then West Germany. In 1973, Peugeot sold 168,909 bicycles in the United States. Foreign models were highly desirable in urban cosmopolitan markets, and Peugeot bicycles selling from $100 to $250 were some of the most sought after imports. This was probably due to the lower number of Peugeot bicycles imported to the United States compared to other foreign brands, the success of the Peugeot racing team in the Tour de France during the 1960s, and the ability of consumers to purchase the same bicycle as used by the pros. The number of Peugeot bicycles sold worldwide in 1975 dipped due to social unrest, a shortage of manpower and parts, declining sales in the United States, and new competition from other countries such as Italy. When M. Bernard Thevenet won the Tour de France in 1975, French bicycle manufacturers hoped that their sales would recover. Although the number of Peugeot bicycle sales did modestly increase in France, international sales remained flat through the remainder of the 1970s.

Data from Hilger 2004

References

- Anderson, H.; Lord, M. “Pedal power.” Newsweek 2 July 1979: 59.

- Anonymous “Bike Boom Rises to its Christmas Best.” Business Week 21 December 1968: 44-46.

- Anonymous. “They Like Bikes.” Time 14 June 1971: 81

- Anonymous. “Bike Boom: A Way Out for Commuters.” U.S. News & World Report 6 December 1971: 84-85.

- Anonymous. “The Bike Boom Leads to Another Trend – More Bike Thefts.” Business Bulletin 1 July 1971): 1.

- Anonymous. “Pedal power.” The New York Times. 17 August 1972: 34.

- Anonymous. “Bicycle Boom Still in High Gear.” U.S. News & World Report. 5 November 1973:88

- Anonymous. "Bernard pedals for France." The Economist. 26 July 1975:90.

- Anonymous. “Bike Boom Pedals into High Gear.” U.S. News & World Report. 19 December 1977: 69-70.

- Anonymous. “Bicycle Boom Levels Off; Dangers, Driver Resentment are Cited.” The Washington Post 4 September 1977: A16.

- Anonymous. “The Bicycle Fights Back.” The Globe and Mail (Canada) 10 July 1978.

- Anonymous. “A Guide to Bicycle Shopping.” Business Week 9 July 1979: (Personal Business Section) 84.

- Anonymous. “Adapting Bikes to New Buyers.” Business Week 10 September 1979: 40H.

- Bender, M. “Bicycle Business is Booming.” The New York Times (15 August 1971: F1 & F4.

- Brecher, J.S. “Perilous Pedaling: The Boom in Bicycling Brings With it a Surge in Accidents and Deaths.” The Wall Street Journal 15 August 1972: 1 & 31.

- Burden, D. "Bikepacking Across Alaska and Canada." National Geographic May 1973:682-695.

- Campbell, J. “In the Wake of the Bike Boom, an Accessory Avalanche.” Sports Illustrated 5 July 1976: 48-51.

- Cross, K.D. “Bicycle-safety Education: Facts and Issues.” AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety. Falls Church, VA. 163 pp.

- Grove, N. “Bicycles are Back, and Booming.” National Geographic May 1973: 670-681.

- Hand, A.J. “Big Boom in the Hot New Bikes.” Popular Science July 1971: 72-74+.

- Heldreth, H. “Hooray for the Bicycle Boom.” Parent’s Magazine & Better Family Living April 1972: 48-49+

- Hilger, L. 2004. "Peugeot et le Cyclisme." Saint Paul, Luxembourg. 191pp.

- Lindsey, R. “Thieves Follow Tracks of U.S. Bicycle Boom.” The New York Times 27 August 1972: S26.

- Robertson, N. “With Health and the Environment Trends, Adults Swing to Bicycles.” The New York Times 17 May 1971: 39.

- Shannon, M.J. “Bicycle Makers Rolling Up Record Sales as Adults Discover New Way to Keep Fit.” The Wall Street Journal 7 October 1965: 32.

- Sloane, E. 1970. "The Complete Book of Cycling." Trident Press, NY. 342 pp.

- Star, J. “Bike Boom.” Look 1 December 1964: M14.

- Stewart-Gordon, J. “Bike is Back and Booming!” Reader’s Digest December 1971: 185-188+.

- Thiffault, M. 1973. "Bicycle Digest." Digest Book, Inc. Northfield, IL. 287 pp.

- Wade, B. "Bicycle Buyers Outrace Supply." The New York Times 11 November 1972: 43 & 45.

|